On March 27, 1964, a converted liberty ship named the SS Chena brought a shipment of supplies to the port of Valdez, Alaska. Valdez, which I need you to know is pronounced “valDEEZ,” sits at the end of a fjord—a narrow inlet carved by a glacier. The town accreted there, more than being carefully sited and built, mostly as a result of a massive gold-rush scam. It’s the northernmost ice-free deepwater port in the US, which makes it important, but it’s a tiny town: in 1964, only about 1,200 people lived there. When the Chena arrived for its regular supply delivery, people gathered at the dock to watch it, and to catch the candy and oranges the crew always tossed out to the kids.

A little while later, about 15 miles underground and 40 miles away, the pressure that had built up along the Aleutian subduction zone erupted, letting the Pacific tectonic plate shove a little further under the continental North American plate.

The resulting megathrust earthquake was a 9.2 in magnitude—the second-strongest recorded on Earth. It reshaped the science of seismology and provided new evidence for the then-tentative theory of plate tectonics. More immediately, it caused parts of the Alaskan coast to rise nearly forty feet, dropped others below sea level, triggered enormous tsunamis, and rang the planet like a bell.

Most of the territory affected by the quake is barely populated, but a hundred and thirty-nine people died, most of them in local and distant tsunamis. Down the Oregon Coast from where I live, four children and a family dog camping on the beach with their family were swept out to sea and drowned. Much of Crescent City, California was destroyed. Rivers sloshed as far away as Texas and Louisiana.

Something else happened in Valdez. The town was built on glacial moraine, a silty deposit of disorganized debris left behind by the ploughing march of a glacier. Near the shoreline, this jumble of unconsolidated rock and sand went down for 600 feet. And the ground was very, very wet. The water table was only a few feet below the surface of the town, and in late March of 1964, between that barely-subterranean water and the melt from Valdez’s extraordinarily heavy snows, the ground was as sodden as soil gets.

Under normal conditions, even wet, disorganized soil will hold up things like buildings and people because the contact forces between solid particles let them transfer weight down into bedrock or denser soil below. But we know now—in part because of what geologists learned from the ʼ64 earthquake—that when strong, sudden shocks hit loose, saturated soil, they can compress the water that fills the gaps between all those loose particles. When the shock is strong enough, the water pressure exceeds the forces holding the solid particles together and the water just…wins. The soil stops behaving like a solid and liquefies, and this happens all at once. Buried things like sewer pipes rise up and erupt through the surface, and things on the surface fall in. All that is solid melts into flow.

Crew members on the Chena who’d been filming locals and shipmates goofing off caught blurry 8mm footage of the earthquake’s arrival in Valdez harbor. Until last year, members of the public had seen the Chena footage only in mutilated form—cut up, remixed, and spiced up with unrelated footage for dramatic effect. The original version has been lost, but in 2024, a US Geological Survey team reassembled the surviving fragments of the footage and added commentary and visual annotations.

The film is blurry and grainy and not graphic in the sense that you won’t see people dying on camera. I’ve seen it a whole bunch of times—both the chopped-and-screwed version and the new restoration. I think it is the single scariest thing I have ever seen.

One of the most consistent reports from people who survived the earthquake in Valdez is that when the shocks hit the town, the ground rolled and heaved like waves, breaking streets and collapsing buildings. Worst of all, an underwater landslide a mile wide opened up at the shoreline. The solid ground under the harbor just melted away. Docks and buildings and everyone on and in went over the edge of a brand-new underwater cliff.

Two blocks of the town—about 75 million cubic meters of moraine—fell into the harbor. The resulting tsunamis rose 170 feet above sea level in an inlet just over from Valdez. That’s twenty stories high. In and around the harbor, 32 people were killed.

Gradually and then all at once

I’m writing this post to talk about what is happening to the way we know things.

All this year, as I have chewed my way along the edges of this almost unfathomable problem, what happened in Valdez came to feel less like a metaphor and more like a model. That’s how I’ll work with it here. Not because the circumstances of megathrust earthquakes in fjords are literally the same as the societal problem of collective derangement, but because the model gives me new ways to take the problem apart and see how the pieces interact.

If I dumb the seismology down to my epistemic-trespasser level, those pieces are, roughly:

- the jumbled, loose substrate at the end of the Valdez fjord;

- the total saturation of the ground which, under sufficient pressure, forces soil particles apart and turns previously solid foundations fluid; and

- the shocks.

This post is not a provocation so much as a report-back from the fragmented thinking that has bubbled up around my research and the thousand-odd hours I’ve put into information mutual aid work over the course of this year. And it’s also a look forward—not at our future, which I refuse to try to predict, but at some paths I think we might want to explore.

Loosening the ground

Human knowledge is always collective—more literally than I think most of us want to admit. I’ll get into the uncanniest parts of that territory a little further in, but I want to stake out the idea that we build our understanding of the world together, from information assembled by others and then held in common. Where in common includes what’s in our own individual brains and what’s in the brains of others and what is in our species’ vast apparatus of extended collective mind, including all the libraries and archives and crumpled paper manuals and tax form instructions and phone videos of dudes fixing appliances.

A cartoon model of collective knowledge-making goes like this: Some people—scientists, reporters, scholars, fixers and builders—go out and mess around with the surfaces of the world and return with artifacts like papers, datasets, reported stories, recipes, hacks and tricks and tips and workarounds. And then the rest of us turn those artifacts into knowledge by making sense of them in the context of everything else we think and know. Expert knowledge production goes at the foundation of things like medicine, engineering, and physics and inexpert, marginal sensemaking swirls around those foundations, ignored by most people, at least when it comes time to do something serious. It’s all much messier than that and the experts are often terrible and wrong, but bear with me.

Marginal sensemaking communities—the ones that break the rules meant to keep mismatched frames like theology or mysticism out of zones like scientific inquiry—have always flourished in America, and not only in the discipline of economics. They’ve famously produced dire stews of pseudoscience and heresy: Proto-televangelist Father Coughlin’s racist American fascism is an obvious avatar of our own age. I think also of the still-formidable Oprah Winfrey who, with her less personally gracious imitators, steered decades of daytime television audiences into and through a Boschean landscape of satanic ritual abuse, the Law of Attraction, vaccines causing autism, and pseudo-medical nonsense of every kind.

And here in the US, the distinctions between respectable and marginal sources of information and sensemaking on top of information have been eroding for decades. Among other things, I’d argue that this erosion has allowed highly motivated actors to draw marginal forms of knowledge formation—baseless conspiracy theories, cultic and magical thinking, Nazism, grifts—closer to the center of civic life. In our late age of the world’s experience, the erosion has put unqualified conspiracists on federal vaccine evaluation panels and Oprah-favored supplement-peddling weirdo Mehmet Oz at the helm of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

And yes: this was happening long before the internet, but the internet’s arrival produced enormous increases in scale. And sometimes a difference in scale becomes a difference in kind. I think the mature, global-scale form of the social internet—which I think really got going between 2008 and 2012—accomplished two things, almost simultaneously:

- First, the big nodes of fundamental information production deconsolidated and scattered like a planeload of marbles dumped onto a frozen lake. Information produced by individuals about their own lives and what they witnessed around them ate away away at trust in even elite news organizations. Massive leaks found global attention and revealed the secret workings of government and military agencies that denied them.

- Second, participants in marginal sensemaking communities gained the ability to find each other—and, with help from algorithmic weirdness, to detach millions of others from large central slow-moving mass sensemaking cultures and recruit them into effervescent quick-turn knowledge-production communities—for good or ill. Millions of people came to a new and more accurate understanding of the prevalence of state violence against Black Americans; millions simultaneously came to a new and deranged understanding of vaccines, public health, and even germ theory.

This is what I think is happening: The knowledge substrate of our society has become increasingly loose and disorganized. It’s now composed of an extraordinary variety of highly disparate things that claim to be news, from vivid and skillful investigative reporting to openly partisan propaganda through the distributed op-ed cultures of podcasters, Substackers, and streamers. The substrate is also enmeshed with “news” organizations devoted to discrediting reporting and with social platforms that deliberately shape the subset of information we see based on our own dumb desires and susceptibility to casino tricks—and on the megaplatforms’ drives toward profit and power. It’s an unstable mess, and we all know it.*

Everything is also just happening too much, and I think we know all that, too.

The flood

The language of natural disasters shows up a lot, mostly in vague but evocative ways, in reporting and academic work on information overload: avalanche, flood, tides, drowning.

We’ve been fretting about information overload—in almost exactly those terms—since at least the early 1960s. (See James Grier Miller’s “Information Input Overload and Psychopathology” [1960] for an early and influential example and James Levine’s “The nature of the glut: Information overload in postwar America” [2017] for a historiographic account.)

The volume of recent scholarship on information overload is fittingly overwhelming, but the part of this research that overlaps with the workings of the social internet is especially relevant and also frankly upsetting.

There is a lot—like a lot a lot—of research suggesting that using social media to keep up with news does not actually inform us but does makes us feel more informed. Many studies of many populations have found for knowledge about what’s happening to us, social media essentially magnifies the Dunning-Kruger effect. When we talk about brainrot, we’re not wrong.†

A few results that especially struck me follow, and each of these papers cite many others, only some of which I got through in my month of intermittent slogging on this. If you don’t want to see the details, feel free to skip this section.

- A widely cited study of German internet users found that exposure to news in social feeds didn’t actually increase the subjects’ knowledge of the topic, whether they included a lot of news posts or just a few—but news feeds with lots of news posts did inflate users’ belief that they were well informed: “Frequent activation of a topic [by exposure to news posts] increases a feeling of knowing, even if actual learning hardly takes place” (Schäfer, 2020, my emphasis).

- Researchers who conducted experiments in Japan concluded that subjects who consumed traditional news were likely to know objectively more while expressing humility about their knowledge, while subjects who used social media to consume news tended to know less while overestimating their knowledge (Yamamoto and Fang, 2022).

- Researchers trying to figure out why people who use social media for news seem not to learn built one explanatory hypothesis around filter bubbles and another around information overload. They first confirmed that indeed, people following news via the social internet did not actually acquire much, if any, knowledge. They found no support for the filter bubble thesis, but did find evidence that information overload is a major factor in the failure of social media information to translate into actual knowledge and that “the more time one spends on Twitter and Facebook for news the more one experiences overload” (van Erkel & Vam Aelst, 2020).

Which, again: We know this in our bodies already. But it’s good to see it confirmed as real, especially since the conversation outside of academia seems to focus so much on personal scolding (what if diet culture but media) or brushing off these concerns as not new and therefore not real.

So we have the disorganized informational ground. And we have a saturated knowledge ecosystem that confounds the formation of durable knowledge. Now I want to look at what happens when you hit a saturated jumble of communal sense with something big and fast and heavy.

The shocks

When a series of shocks that are very big and close together jackhammer into a loose flooded substrate, solid ground liquefies. What I want to talk about here, as briefly as I can, are the increasingly intense, repeated, and relentless shocks that the first and especially the second Trump administrations have administered to our ability to know anything at all.

The first Trump administration was chaotic and overwhelming even before the arrival of the pandemic in the US. The second immediately jumped to another level of magnitude. This week, the New York Times published an interactive feature showcasing how much media attention the president has attracted—including from the NYT itself.

It’s not only the volume of noise, but the instability of the information allegedly transmitted. The president spews millions of words, constantly contradicting himself and spouting ludicrous statistics and impossible math alongside the racism and xenophobia. And the year’s 5,000 (really) presidential shitposts can’t be definitively disregarded nor the bullshit rants classified as meaningless, because the president and the people around him are constantly sledgehammering the norms, laws, rules, and common decencies that have preserved an imperfect but real form of democracy until now.

The White House and cabinet agencies alone produce material for hundreds of stories each day, each hair-raising and chaotic and weird. But it’s not just the noise. The administration is also dismantling every source of ground truth they can get their hands on, from medical research to national intelligence to meteorological data. They forbid government organs even to measure anything related to a laundry list of disfavored ideas. And they have replaced longstanding ways of making careful sense of complex data and replaced them with a propaganda of incoherence.

These attacks on truth, knowledge, and sense are not incidental: They’re at the heart of our leaders’ agenda. As each attack smashes into the jumbled and flooded landscape on which we once made sense, the ground goes liquid and we fall in. The guardrails that prevented almost all of us from openly stating in public that, for instance, we think Hitler was actually a great leader have gone into the water. Norms against collective punishment are gone, along with the ones that forbade open ethnic cleansing. The rules for making respectable sense have, for millions of Americans, dissolved; malignant sensemaking swirls through the flood like sewage, getting into everything.

And I have no data for this, but think a huge number of us who genuinely care what is happening—people who have devoted their time to education, public service, communal care, and the ideals of democracy—have found their sense of the world frizzing into a malicious Lynchian cosmic static. And many, many people turn away from the news as a means of understanding: only 39% of left-leaning Americans follow the news all or most of the time now, down from 49% in 2016. Among right-leaning Americans, the drop-out is much larger: 36% now say they follow the news most of the time, down from 57% in 2016.

But! I think there is something underneath it that is scarier and worse—and through which I, at least, had to go to find a way out.

I’m telling you stories; trust me

Consider, please, a ballpoint pen. Or a sewing machine, or a quartz watch, or a flush toilet. With the exception of a helicopter, which most of us see mostly from a distance, I think these are all items with which most of us are at least passingly familiar. (Maybe not the sewing machine? I don’t know. Let’s go with the toilet, to be safe.)

We are intimately familiar with toilets. We are with them in nakedness and illness and misery. We use them and clean them and sometimes unclog them. Most of us have probably had to open one up and jank around with the contents of the tank, unsticking a sticky flap or reconnecting a slipped-off pull-chain. They show up, not infrequently and often in conditions of brokenness or filth, in our dreams. We understand the toilet. Except it turns out that we don’t.

I want to spend a moment on paper called “The misunderstood limits of folk science: an illusion of explanatory depth,” published twenty-four years ago in Cognitive Science. Despite covering similar territory, it’s much less widely known than the Dunning-Kruger Effect, probably in part because it lacks a catchy name. The paper, by Yale professors Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil, describes an set of tight little experiments that demonstrate that—generally speaking—we can’t actually describe the workings of the world around us, though we believe we can, until we’re forced to try. If you like to read journal articles, I can recommend this one as a rollicking bad time.

From the abstract:

People feel they understand complex phenomena with far greater precision, coherence, and depth than they really do; they are subject to an illusion—an illusion of explanatory depth. The illusion is far stronger for explanatory knowledge than many other kinds of knowledge, such as that for facts, procedures or narratives.

This illusion of understanding that we use to move confidently through a life enmeshed with irreducible complexity is dispelled only when we force our brains to (forgive me) show their hands: to reveal the actual degree of our usually deeply inadequate understanding. When we try to explain something and fail, we can usually recognize our earlier overestimation and correct it.

When I first encountered the paper some years back I did not do well on my toilet-based self-test, despite having disassembled a toilet. (There is, as it turns out, siphoning going on, along with other things. What?)

I found this intensely alarming not because I’d fail out of plumbing academy, but because I’d been pretty confident in my sense of a toilet. If I don’t know how a toilet works, what else am I missing? Almost everything, offer Rozenblit and Keil. Most of the explanations that I think are in my brain are actually dotted lines in the shape of real explanations, but with very little inside them. They are ghosts of knowledge. And I won’t know what I don’t know until I fuck around and find out.

I turn out to be a more than usually “reflective” person, which is to say that I am underconfident in the extent of my knowledge, compared to the norm. So accepting that there are gaps everywhere in my knowledge is pretty easy—especially now that I’ve released most of the vestigial confidence in my brain that got me through my 20s. But accepting that there are gaping holes in my knowledge that my brain hides from me is about as much fun as larping Un Chien Andalou.

So: Even those of us who think we know things and believe that we’re “paying attention” know far less than we think we do. We are mostly skating on a brittle scrim of knowledge over an unperceived void, blithely trusting the resources around us to fill in for our spotty brains on a just-in-time basis.

I think this phenomenon feels most real when something familiar—a machine or system or, worst of all, the behavior a person—goes badly wrong. If we’re isolated, we attempt to call on our understanding to begin repair or even just analysis, and the machine or system or person turns to us a stranger’s face. A particular sinking horror intrudes, scaled proportionately to whether the broken thing is a pen or an aortic valve or a marriage.

This feels very bad, so mostly we google.

There are a lot of persuasive papers and books kicking around about social cognition, and the ones I’ve read so far land in essentially the same place. We mostly don’t know things, even though we believe we do, and this is mostly okay because we can either learn things as needed, as when we flip to YouTube to search why knenmore clothe dyrer make terrible scream bd smell, or simply rely on the knowledge of others, as when we need an aortic valve repair or a divorce.

The problem with all of us being so much more a hive mind than we realize is that knowledge problems that ripple across our a information ecosystems can become not just threats to individuals with weak character or bad habits, but the equivalent of colony collapse.‡

A conclusion goes here (#wontfix)

What emerges for me from my year’s shambling passage through earthquake thinking and my babybrain review of scholarship about the social internet and our ability to know things is this: We are very literally in this together—inextricably, more than most of us would prefer to admit, and in ways that make finger-wagging at individuals actively stupid.

Our understanding is only lightly present in our own brainmatter, and exists mostly out there in our loose and jumbled substrate, swept around by floods and tides we rarely fully perceive, let alone control. This suggests unpleasant things about reality: That together, online, we drown others and are ourselves drowned. That our sense of individual knowledge is ghostly: transient, hollow, and occulted.

But it also means that to care about and tend to our dissolute knowledge systems can be to care for and tend to our own understandings—not just to paternalistically seek to march other people forward like pawns toward attitude formation and political activation in ways we think are good. It is to de-instrumentalize our understandings of one another and to assume a position of greater humility and responsibility, together. Real belief in collective knowledge may also suggest that caring for our own knowledge formation in social systems is a way of caring for the system as a whole. Necessary, if not sufficient.

And I haven’t give up on the value of bringing knowledge into our brains and our bodies. There is a spooky power in having things by heart; knitting knowledge well into our minds changes us. As a beloved friend noted when I was rat-scrabbling around the edges of these ideas, to learn something well is to make friends with it—or to be in relationship with it, at least. Ghostly index cards in the brain referring out to the slurry are better than nothing, but I want more and I want it for everyone else, too.

Tracks through the marsh

If you’ve read almost any of my work in the past five years, you’ll know that I try to work backward from our built and natural environments to think about what we do in networks. This is a practical choice, not an aesthetic one: I am leaning on our most ancient faculties and instincts as a species that chose to come indoors, build villages and cities and networks of trade, and to try to not murder each other very much.

There is a staggering store of knowledge about how humans have tried to live together, know things together, and make it through ghastly times intact. And I think there is enormous value in cautious but wide-ranging epistemic roaming to retrieve—and ideally to illuminate—ideas from our social past that might be helpful to us now, as we grapple with problems whose parts are not entirely novel. Salvage from the wreckage, you know?

I undertook the research and practice that forms the substrate of this post both because I needed better knowledge and because I wanted to know what I most want to know. If I were a fancier person, this would be my research agenda. Since I’m not, it’s just a promise to try to haul some specific things up into the light and lay them out where we can use them to try to do better.

Here are a few I’m thinking about the most.

Foundation densification

Thinking about our moment in earthquake terms lets me think about damage mitigation tactics. One of the things you do when you’re building collapse-resistant buildings on a shifty substrate is densify the ground, through compression or binding material (like concrete) or clever sub-foundation scaffolding.

I’m thinking a lot about information densification and retrofitting might look like. All year, in my work at Unbreaking, I’ve found myself falling back on the need for durable knowledge that resists the flood and flow of social streams or feeds, and that can be returned to over time, and on which good interpretations can be built.

Since the spring, we’ve been building and updating chronological timelines that just (“just”) track what happened when in a given zone of American life, and how our best journalists wrote about it at the time.

And let me say: Chronological timelines are about the least innovative and least sexy or funding-attracting thing imaginable, but like…go try to find them, for the things happening now! They’re hard to find and hard to make and hardest to maintain. Yet without an easily referenced record of when the many things happened, we’re extraordinarily vulnerable to doctored, adulterated, and just made up summaries of even extremely recent history. The subsequent mass misbeliefs can feel, to people who were closely tracking the realities being reinterpreted, like the results of mass hypnosis.‡

I think there are many other ways to densify information and make knowledge durable—and that people who work on the social internet should be thinking about how they can work toward that in their systems, in ways that also respect people’s desire to retain the orality or ephemerality of some communication. This is one of the things I’ll be digging down through in the coming year.

Valdez, for what it’s worth, up and moved the whole town.

More clues

At least one of the papers I read about knowledge formation in networks dropped some intriguing clues about the problems posed by mixed contexts and confounded intentions when people come to social media and encounter news they weren’t looking for, and maybe didn’t actually want. This feels like a fruitful and practical path for exploration, maybe in conjunction with something like Tyler Fisher’s Sill.

Several of the papers I’ve been working through discuss the role of cognitive elaboration in the creation of durable knowledge. Cognitive elaboration is, very roughly, synthesizing new information with other knowledge or otherwise playing around with information as a way of knitting it into our minds in ways we can use. This is an obvious springboard for the kind of facile, thought-leader-scented solutions institutions adore (all articles are now quizzes!) but I think it’s also fruitful territory for more sophisticated thinking and experimentation.

Critical ignoring has come up several times in my explorations since my crimeing partner Liz Neeley first sent me a paper about it. I’m also very interested in trustworthy catch-up tools that perhaps use machine learning but are not chatbot summaries. A lot of my work this year has been briefings and explainers on top of timelines as a resource for people who need to just drop the rope—and then, when they’re ready, return and catch up without having to go out and wrestle the shrieking backlog themselves. I don’t think we’re all the way there yet, but we’re learning a lot.

The strongest throughline of my year has been the work of orientation. For myself, for my kid, for my friends and colleagues, and for my weird and only sometimes overlapping communities. Now I’m going to lie flat under our Christmas tree for two weeks, and then I’m going to get back up and see what I can learn.

Thank you

The people who support my work through wreckage/salvage are the only reason I can write my way through these ideas or do the hands-on work at Unbreaking. I am so grateful. If you want to support this work, you can do that monthly or with a one-time gift. It means more than I can reasonably say.

Thank you also to my partner, Peter, for telling me about the earthquake in Valdez, his hometown; for showing me the footage for the first time; and for showing me around Valdez twenty-five years ago. And also for being my thinking partner and first reader. And thank you to my kid for the superb snack plates and for not hollering at me for missing the first three days of winter break.

Update, Dec. 24, 2025: Thank you also to my distributed accidental volunteer copyediting team, you are the most generous and I appreciate you. Many tiny corrections have been made.

Notes

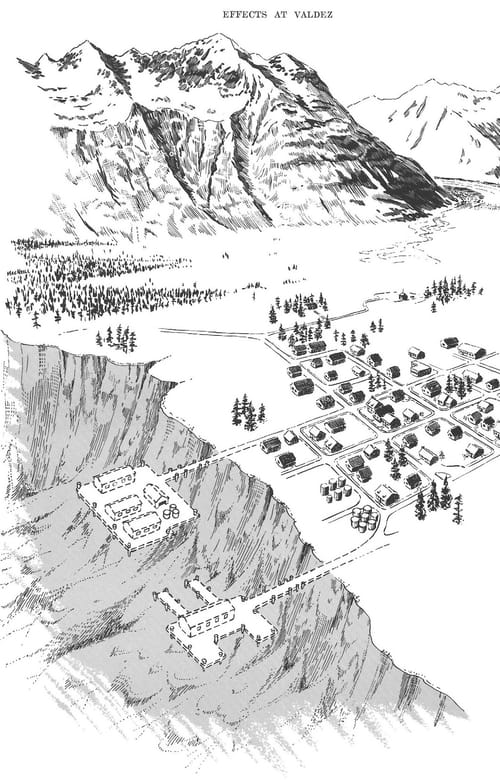

I took this post’s featured image from the USGS report, “Effects of the earthquake of March 27, 1964, at Valdez, Alaska,” which is extraordinary reading and part of a larger set of reports on the earthquake. The report is credited to Henry Welty Coulter and Ralph R. Migliaccio. The image, which is captioned, “Submerged slide ares at Valdez. Dashed lines indicate dock area destroyed in earthquake” and credited to David Laneville of the Alaska Department of Highways. You can find it on page C11 of the report.

Earthquakes and tsunamis are always on my mind because of where I live, on the Cascadia subduction zone, which is the one Kathryn Schulz correctly scared us all to death about back in 2015. Our house is in a tsunami evacuation meetup zone, and I think about that all the time.

Endnotes

* I’ve mentioned Renée DiResta’s Invisible Rulers before, but as someone who grew up inside marginal sensemaking communities that were the direct pre-internet antecedents of the propaganda bubble–manufacturers DiResta describes, I find it the best survey of that terrain I’ve yet encountered. I also think a lot about Henry Farrell’s sense of “publics with malformed collective understandings.” I have been simmering on his post all this year, in roughly the way of a forgotten jar of kimchi gathering menace at the back of the fridge.

† Grimly, the research I’ve been looking at focuses on effects in play before generative AI really kicked in, so this was happening when we mostly just had human-scale nonsense to deal with.

‡ If it sounds like I’m talking about J6, well sure I am. But I’m talking just as much about the wholesale misrepresentations of fact that scaffold the center-left reassessment of the US covid response—and the extraordinary lack of scrutiny those misrepresentations received across the mainstream press. (I apologize for recommending a podcast, I know everyone allegedly hates podcasts, but the If Books Could Kill double-episode fisking In Covid’s Wake is extremely good. Or at least the first parts of each episode are—for all I know, the second halves are just banshee screams, because I got too angry to finish either of them.)